Divergence in UK/EU Environmental Policy:

State of Play 2025

Toby Perkins MP

Chair of the Environmental Audit Committee

Foreword

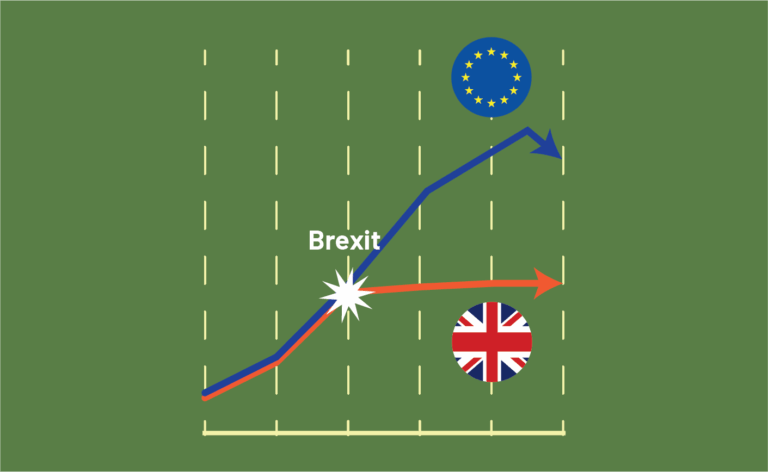

Leaving the EU was a seismic shift for the UK – resulting in rifts that posed risks, but also offered opportunities for the UK to increase its ambition. Environmental policy was one area in which Brexit opened possibilities for benefits for the UK.

Five years after Brexit, the upheaval is settling and the changed landscape is becoming clear. As the chair of the Environmental Audit Committee, we are keenly scrutinising the Government’s plans and policies in the wake of leaving the EU. This report provides a timely and insightful overview into the state of environmental policy in the UK and EU.

Despite some areas in which the UK has actively and positively diverged from EU policy, for example the UK Government’s decision to protect sandeels in the North Sea and the introduction of Biodiversity Net Gain, these instances are relatively rare. For the most part, the UK has fallen behind on environmental and climate policy on circular economy, toxic chemicals such as PFAS, and deforestation.

The risk of regression also remains. The Planning and Infrastructure Bill, which the Office for Environmental Protection has stated amounts to a regression in environmental law, is currently progressing through Lords stages. In its current form, it could undermine well-established nature protection laws. The key challenge for policymakers is to ensure Britain does not become a laggard on environmental standards, without losing the benefits that independence from EU policymaking affords.

Looking ahead, the divergence in environmental policy between the UK and EU will continue to widen. This report helps identify the risks in this growing gap, as well as the opportunities to increase ambition in environment and climate policy.

Key Messages

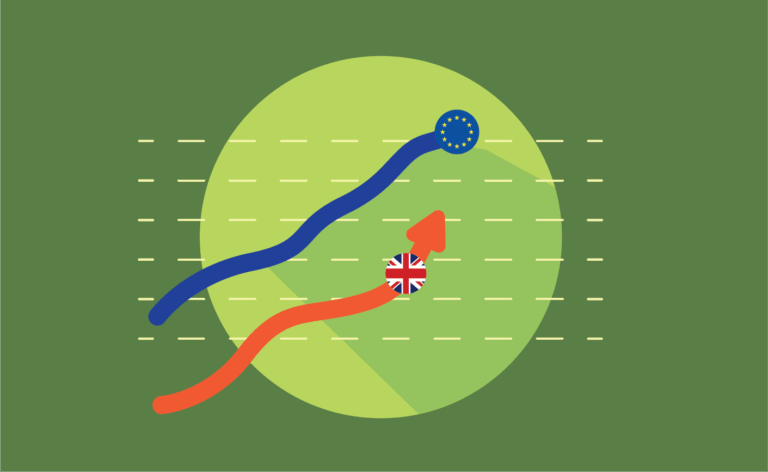

The UK has fallen behind

Five years after Brexit, the UK has been outpaced by the EU in strengthening its environment and climate related laws and policies. In short, the UK has fallen behind in a number of areas and chosen not to keep pace. The UK has mainly ‘diverged by default’.

Common Rulebook divergence

The common ‘rulebook’ on environment and climate policy that the EU and UK once shared up to the point of Brexit in 2020 has been significantly amended by the EU. The EU have tightened up existing laws (the ones UK shared with the EU when a member) but has gone further by creating altogether new laws in a range of areas which deliver higher standards and protections for the environment and climate such as on circular economy, industrial emissions and urban wastewater treatment and deforestation. Many of these are coming into effect over the next few years which will widen the divergence gap from where it is now.

Economic growth takes priority

Looking ahead however the overall picture is becoming less predictable and mixed. Both the EU and UK are preoccupied with economic growth. This has often and unnecessarily been translated into ‘regulation = bad’ and ‘environmental protections = blocking economic growth’. This narrative threatens positive and progressive actions taken by governments of all colours on both sides of the channel over recent years. The two are not mutually exclusive and economic growth is, in many sectors, driven by the green agenda, and is reliant on a thriving natural environment.

Sandeel protection in UK waters: a major win

However, there are some bright spots, most notably the UK and Scottish Governments’ decision to protect sandeels. This is a major win for the environment, and a relatively rare example of the UK Government actively diverging from the EU but using its post-Brexit independent policy making powers in a progressive way.

Brexit hasn’t yet translated into a widespread weakening of environmental laws

The UK has not, by and large, regressed from the levels of environmental protection that were in place in 2020. In other words, the UK does not, broadly speaking, have weaker laws than were in place when it left the EU. However, the spectre of regression hangs heavy. The current version of the UK Government’s Planning and Infrastructure Bill is a major threat that would undermine well established nature protection laws. Unlike the sandeels case, this would be using post-Brexit independent policy making powers to move in the wrong direction.

Pragmatic and constructive relations between UK/EU

The relatively recent return to pragmatic and constructive relations between the EU & UK are a welcome move towards easing tensions and potentially reducing unnecessary levels of divergence in environment and climate policy. Building on the most recent example, the UK-EU Reset, both parties should now go farther and faster.

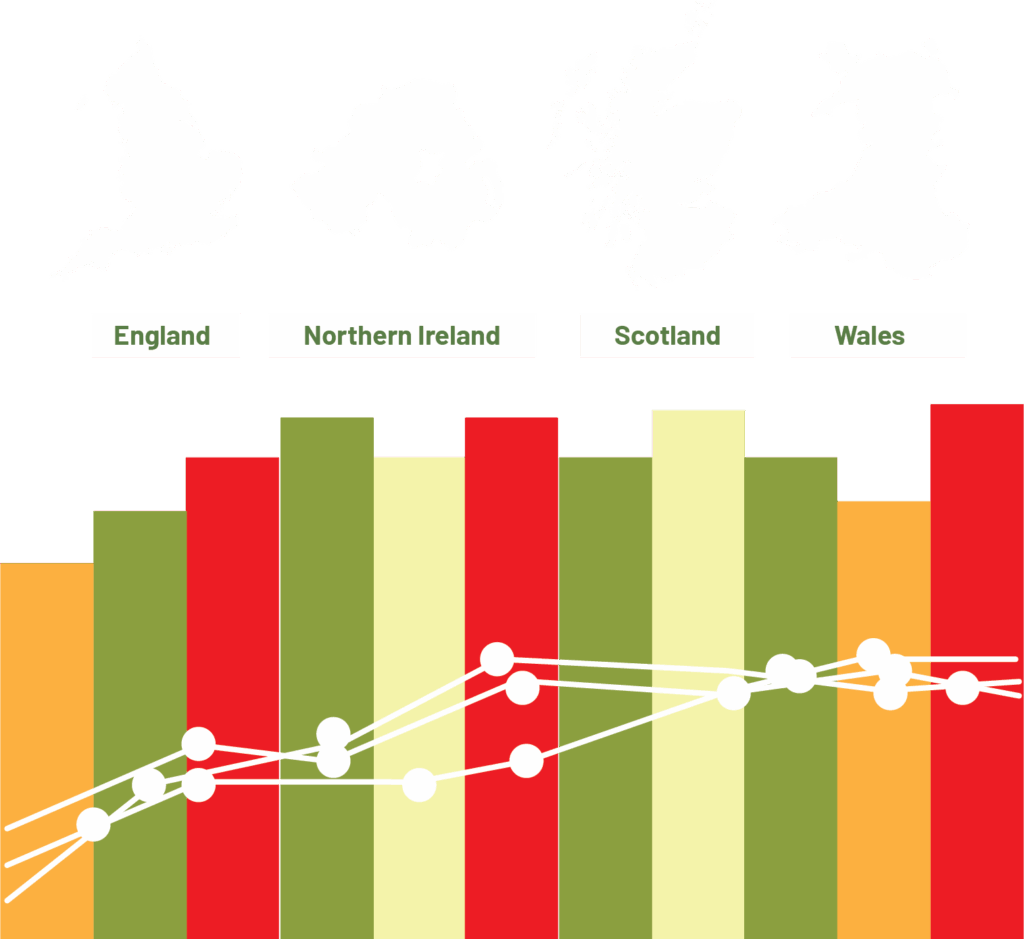

UK/EU Divergence Overview

Air

Agriculture & Land Use

Chemicals

Circular Economy & Waste

Climate

Marine

Nature & Biodiversity

Pesticides

Water

England

N. Ireland

Scotland

Wales

Green: indicates areas where policy has been more progressive than EU policy

Yellow: indicates areas where policy is broadly similar to EU policy

Amber: indicates areas where policy is not keeping pace with more progressive EU policy

Red: indicates areas where there has been regression since Brexit

Information last updated in July 2025

Explore UK/EU regulatory divergence on environment by thematic policy area

What does IEEP UK Call for?

UK alignment with higher EU standards

With the UK seeking to remove trade barriers to aid economic growth, there is an opportunity for higher UK environmental standards, most notably through alignment on product standards, chemicals, several aspects of circular economy policy and deforestation regulation. There are also other areas where we would like to see greater ambition from the UK to ‘catch up’ and ideally overtake the EU – most notably around air, water quality, industrial emissions and nature restoration policy.

Scientific and technical collaboration

The UK and EU should remember that many environmental issues are transboundary – the environment knows no borders. A solid first step to tackling shared problems is ensuring both sides agree on what data and information is telling us about the state of the environment. To this end, the UK should rejoin the European Environment Agency and Eionet.

Increased cooperation on international environmental issues

The UK should increase the priority given to cooperation on international environmental issues, including joint positions and sharing longer term perspectives and plans, for example at global COP meetings. Working through existing forums, set up for example through the Trade and Cooperation Agreement, is helpful but more frequent exchanges of information are required and a further loosening of the operational constraints between officials working on policy files would help.

Learning goes both ways

The EU should continue to learn from the UK, which has enormous experience in formulating and applying progressive environmental policies. Various aspects of recent agriculture and biodiversity policy (e.g., Environmental Land Management Schemes and Biodiversity Net Gain) as well as marine policy (e.g., marine protected areas and protection of sandeels) are good starters.

Higher overall levels of ambition

Whilst our report’s conclusions relate to levels of regulatory divergence, our recommendations are not for blanket alignment for the sake of it. UK alignment with unambitious, ineffective EU policy – or indeed reversals – would be of no benefit to the environment. Equally, we need policies that match the scale of action that is required to tackle severe land and marine degradation, habitat and species loss and achieve our Net Zero targets. The UK should aim high and re-take the lead in all areas of environmental policy and, in doing so, inspire a ‘race to the top’.

UK/EU Divergence Thematic Policy Areas

Across areas such as agriculture, chemicals and water, the UK and EU have taken divergent regulatory paths since Brexit. In this 2025 State of Play report, IEEP UK has conducted an in-depth analysis of UK/EU divergence across nine major thematic policy areas, which you can explore through the following links.

Download the full report