Authors: David Watts, Marianne Kettunen

The COVID crisis has been a concrete lesson on the interdependency between the different elements of sustainability – from ecosystem integrity to health and wellbeing and the socio-economic prosperity that follows. The response to the crises needs to be equally all-inclusive, with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) providing a suitable framework.

The 2019 Global Sustainable Development Report highlighted that we were not on track to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), calling for more substantial and accelerated action to bring about the transformative changes necessary to achieve Agenda 2030.

The annual Global SDG Index by the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN) reached similarly damning conclusions on the lack of political commitment, highlighting alarming downward trends in climate (SDG 13) and biodiversity indicators (SDGs 14 and 15).

Against this sobering backdrop, the COVID-19 pandemic is now having a significant negative effect on sustainable development efforts worldwide.

The initial official United Nations (UN) response to the current crises recognised the lack of preparedness for its consequences and, rather blatantly, stated that “had we been investing – [in] MDGs and SDGs – we would have a better foundation for withstanding shocks”. The UN also warned of the short-term nature of reduced carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere and called for an SDGs focus as we rebuild.

| Rather than resorting to protectionism, the UN has called for continuing to build on trade as an opportunity for global prosperity |

Moving forward, the UN identified several concrete policy recommendations to help to achieve an SDG-focused pathway to rebuild, advocating for the implementation of “human-centred, innovative and coordinated” stimulus packages.

Rather than resorting to protectionism, the UN has also called for continuing to build on trade as an opportunity for global prosperity – and now also as a means for recovery – while supporting developing countries financially and organisationally so that no one is left behind.

In its desired response, the UN has recognised that the fragility of supply chains revealed by the crises should be addressed by strengthening approaches that enhance both resilience and efficiency, including circular economy and climate action.

The United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) has further specifically focused its attention on the environmental aspects of recovery, calling for ecosystem-based approaches to achieving the SDGs, including tightening policies to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and protecting biodiversity to contribute to a lower likelihood of future pandemics.

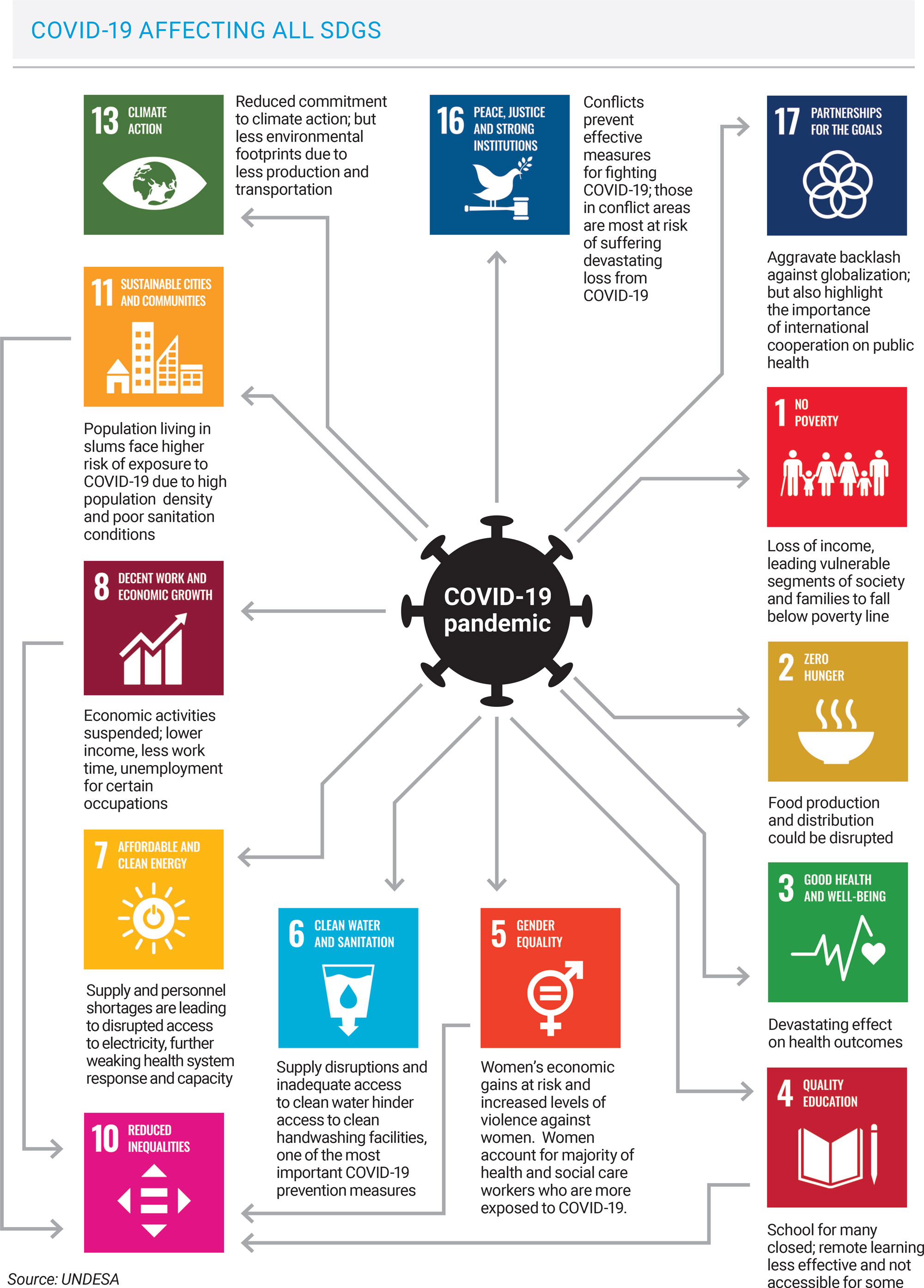

Identified impacts of COVID-19 crises across the SDGs (high-resolution), as shown in the UN report Shared responsibility, global solidarity. Image © United Nations Identified impacts of COVID-19 crises across the SDGs (high-resolution), as shown in the UN report Shared responsibility, global solidarity. Image © United Nations |

This “green position” has also been endorsed from the top, with the UN Chief Executives Board (CEB) recently underlining the connection between people, nature and climate and recognising the need for a stronger focus on nature across the UN system. This commitment would be solidified through developing “a common approach to integrating biodiversity and nature-based solutions for sustainable development”.

But – are countries and other actors taking up these calls, and are we seeing any focus on the SDGs and rebuilding on the 2030 Agenda as a response to the crises? Or has the COVID crises put a final nail in the coffin for Agenda 2030, with countries focusing on economic recovery only and turning a blind eye to the interdependency between different elements of sustainability the crises has revealed?

Are we seeing a focus on the SDGs as a response to the COVID crisis?

The success of the SDGs and Agenda 2030 is dependent on the ability of states to financially support policy transformations. Therefore, the stimulus packages that are put in place now, and how they will be utilised, are perhaps the most important indicator to predict the future fate of the 2030 Agenda.

| So far, the global response from governments and inter-governmental organisations is varied |

So far, the global response from governments and inter-governmental organisations, in terms of the foreseen role of the 2030 sustainable development agenda in economic stimulus packages, is varied – but perhaps with a determined shade of green in the mix. At least on the level of rhetoric.

At the top of the intergovernmental “food chain”, the G20 has yet to collectively commit to any substantive green policies in the post-COVID-19 recovery and has been hindered by the US position at this time – for whom the environment is not high on the political agenda.

A paper by Stern et al. finds that just 4% of policies by G20 countries since the pandemic have been ‘green’, highlighting the extent to which more can – and should be – considered by policymakers in an SDGs focused recovery. Similarly, the G7 have focused their attention on the immediate response to the pandemic, with some consideration of economic growth thereafter but with no explicit, coordinated green focus.

President of the European Council Charles Michel participates in the G20 leaders’ video conference on COVID-19 in March Photo © European Union

Within the G20, the EU and Canada seem to have taken the lead on championing green recovery.

Fortunately, the European Commission is not alone on this mission, with climate and environment ministers from 17 Member States calling for a green recovery. The EU puts biodiversity and climate change front and centre of its recovery efforts and has highlighted its focus on strengthening partnerships in the immediate neighbourhood with long-term sustainability ambitions.

Despite calls from some of its Member States, the European Commission has insisted that the European Green Deal – the centrepiece for delivering SDGs in and by the EU – will be an integral part of the EU recovery plan, including 50-55% GHG reduction from 1990s levels and structural reforms within the energy and transport sectors.

| Canada has recently emerged as a leader in green recovery by attaching climate provisions to government loans |

Similar to the EU, Canada has recently emerged as a leader in green recovery by attaching climate provisions to government loans. According to Stern et al., such synergies between climate and economic goals increases prospects for “national wealth, enhancing productive human, social, physical, intangible, and natural capital.”

Canada, with its G20 partners Italy and Brazil, has also stepped forward in support of the UN system on food security, calling for a global and long-term response, also stating that “strengthening the fundamental nexus between humanitarian assistance and sustainable development will also be crucial”. However, we are yet to see these countries respectively commit to policies that enunciate this statement.

Green pathfinders to recovery are also emerging outside the G-country blocs, going beyond the rhetoric. New Zealand has recently announced a $1.1 billion commitment from the 2020 budget towards restoring the environment, including with an expectation of creating around new 11 000 jobs.

The immediate response in Asia has been heavily focused on the immediate threat and as of now, many nations have remained tight-lipped on recovery mechanisms with green ambitions.

While it is true that many communities in Asia are highly vulnerable to the pandemic, the states also certainly have the resources to commit to a green recovery that brings with it greater preparedness for future shocks.

South Korea, however, provides some hope with an EU-style green deal forming part of the manifesto of the newly elected Democratic Party; being heavily reliant on coal, this is a promising and encouraging step for the Asian nation.

In China, meanwhile, the National People’s Congress (NPC) has made the recovery from COVID-crisis a key item on its agenda.

Photo © UN Photo/Mark Garten

Several international funding organisations have also stepped forward with explicit support to the green recovery.

For example, Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) Kristalina Georgieva has called for utilising all available levers to enable a green recovery, including using public funding to promote green private finance and secure long-term commitments to low-carbon alternatives.

| Genuine interest in green transformation as a response to the COVID-crises is also seen at the local level |

In a similar vein, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) has stated that counteracting the pandemic creates an opportunity to “tilt to green” the large-scale recovery spending being pledged, making this a key accelerator towards a low-carbon economy.

Both the African (ADF) and Asian (ADB) development banks, however, have focused their attention on providing economic support (e.g. securing employment) without specific considerations for an SDG-oriented or green recovery.

Finally, and beyond international and national governance, genuine interest in green transformation as a response to the COVID-crises is also seen at the local level, with the emphasis on supply chain innovation pointing towards more sustainable and resource-efficient production chains.

This ambition can be fulfilled with increased attention to circular economic thinking, which we are beginning to see commitments to. For example, Amsterdam has announced ambitious plans to base its recovery on a ‘doughnut’ economy, in line with SDG 12 and championing the green focus in the recovery from COVID-19.

Towards the UN High-Level Political Forum 2020

In May, the UN Secretary-General released the annual SDG Progress Report for 2020. The report confirms the devastating impact of COVID-19 on the achievement of the SDGs, particularly in the case of the least developed and developing states.

The key message of the report is that “progress is stalled or reversed on inequalities, the rate of climate change, and the number of people going hungry”. The report echoes the earlier UN call to action for inclusive and sustainable development following the pandemic, that will protect recent gains, and help to meet the goals of Agenda 2030 and the Paris Agreement.

| Progress is stalled or reversed on inequalities, the rate of climate change, and the number of people going hungry |

The UN High-Level Political Forum (HLPF), representing an important annual stocktaking opportunity on the progress towards the 2030 Agenda, will be held in July with focus on all 17 SDGs and identifying pathways for the transition to sustainable development. Under the current circumstances, it is likely – although not officially confirmed – that the forum will be mostly held virtually.

While the nature of foreseen debates and policy outcomes is still unclear, we understand that the 51 states originally scheduled to present Voluntary National Reports (VNRs) are still eager to do so in 2020.

Thus, the HLPF will still be an important arena to share and debate information and to emphasise the implementation of Agenda 2030 in the post-COVID-19 era. It will provide a natural (online) forum for bringing together the global discourse on the future of the SDGs, including a place to put governments under the spotlight in terms of concrete plans for keeping Agenda 2030 alive and reigniting their interest in more holistic approaches to development.

In light of the SDG 2020 progress report findings, the HLPF must, in particular, stimulate discussion specifically about how to address the negative progress in areas including climate change, how the most vulnerable communities and nations can be supported, and concrete policy recommendations that will lead to the achievement of Agenda 2030.

The COVID-crisis has been a very concrete lesson on the interdependency between different elements of sustainability – from ecosystem integrity to health and wellbeing and the socio-economic prosperity that follows.

It would seem foolish not to conclude that the response to the crises needs to be equally all-inclusive. The 2030 Agenda continues to provide a suitable framework for such a response, especially on a long-term horizon.

As we take stock and assess critically our own relationships with SDG 3 on health and wellbeing it is critical that we do not lose sight of what still needs to be achieved in this penultimate ‘decade of action’ for Agenda 2030.

A global response to COVID-19 must, therefore, include restated commitments and enhanced mechanisms that bind states to achieve SDG targets. As the UN response highlights, better preparedness for such crises can only be achieved by SDGs – putting us on track towards a more sustainable world, with access to quality health care and more inclusive and sustainable economies.